Say what you will about Elon Musk – his rockets are terrific

How a 1987 article foresaw the new ultra-huge SpaceX Starship

Intro: I’ve taken a couple potshots at Starship, Elon Musk’s gigantic exploding rocket, which just became zero-for-three on test flights.

A reader wrote to advise me I should look up a 1987 article about rocketry, which said NASA had lost its way by pursuing expensive max-tech. If we want to get serious about space, the article said, we should build very large but mechanically simple rockets that use steel and low-cost fuels, rather than the exotic materials and advanced propellants NASA favors.

Published 15 years before Musk founded SpaceX, the article called for a new type of rocket: the very kind SpaceX now flies. I found the analysis persuasive. Plus it was by a smart guy – me.

Based on my own 1987 advice, I am switching sides, to become an advocate of Musk’s gigantic booster: officially Starship, known around SpaceX as Big Fucking Rocket.

If you’ve been asking yourself, “When will I see a Substack about rocket science?” the answer is, today!

In the early days of rocketry, advances came quickly. It was just 12 years from America’s first attempt to launch a tiny satellite, in 1957 – the rocket exploded a few feet above the pad – to Neil Armstrong walking on the moon.

The Vanguard, Redstone, Atlas, Titan and Saturn rocket families were developed quickly, with different engineering and fuel choices. Back then Soviet Union developed new rocket families quickly too.

As the Apollo program wound down, there was debate about what sort of launchers to build next. Anyone who’d watched stages of the magnificent Saturn V moon rocket crash into the sea and sink wondered why spacecraft could not be reusable – like in Buck Rogers! Political momentum began to build for the space shuttle program, centered on a winged vehicle that lands on a runway for reuse.

The space shuttle would be possible only with max tech – lightweight components, liquid hydrogen propellant. Design criteria would be maximum performance/minimum weight, the design criteria used for jet fighters. The result would be very expensive, but, the United States government was paying.

A small camp of rocket designers argued for minimum cost in lieu of max tech.

An influential engineer named Arthur Schnitt (1915-2010), at the Air Force think tank Aerospace Corporation, proposed that a rocket which was really enormous but mechanically simple, made of steel rather than composite materials and burning simple fuels such as kerosene, could put weight into orbit for a fraction of the expense of the space shuttle.

A SpaceX Falcon — Little Dumb Booster.

The shuttle program won at the levels of the White House, Congress and Pentagon.

The Air Force has a larger space presence than NASA – Joe Biden’s FY2025 budget proposal asks $25 billion for NASA, $29 billion for Air Force space efforts, rebranded as the Space Force.

Institutional Washington liked the space shuttle because it was max everything, and politicians would want to have their pictures taken standing next to one. Aerospace contractors liked the space shuttle because it would be very expensive, with delays and cost overruns inevitable. Music to the contractors’ ears!

Indeed, building and launching the first space shuttle took longer than building and launching the first Apollo mission. But a cycle of Washington procurement had been engaged: “Too soon to tell, too late to change.”

Max-tech assumptions drove the shuttle program: aluminum-lithium alloys, composite materials, liquid hydrogen. That propellant must be held at -432 Fahrenheit, can waft through the walls of fuel tanks.

The space shuttle was sold to Congress with a promise it could put payload into orbit for $600 a pound. The actual cost turned out to be $30,000 a pound. (All money figures have been converted to current dollars.) NASA and the Air Force spent almost three decades wedded to the technologically impressive, ruinously expensive space shuttle.

The 1987 article. Arthur Schnitt at his desk.

Back in the day, Schnitt had been told that if he hoped to keep his nice job, he would stop saying there were ways to cut the cost of access to space. Washington wanted the public to believe everything about space means higher taxes.

Schnitt was taken off rocket research and reassigned to analyzing bus schedules. (Finding the ideal bus schedule is actually a longstanding challenge in math.) This kept Schnitt away from advocacy of cheap rockets.

Newer rockets designed for NASA and the Air Force by big contractors, Lockheed Martin, Boeing and others, had improved features but did not cut costs, relying on max-tech materials and fuel. Not cutting costs was the program goal!

My article about this ran on August 17, 1987, as a Newsweek cover story. The article was 11 pages – today Newsweek wouldn’t run an 11-paragraph article. So far as I can determine the text is not online; I’m thumbing through a hard copy as I write. Here the old federal Office of Technology Assessment analyzes Schnitt’s thinking and my article.

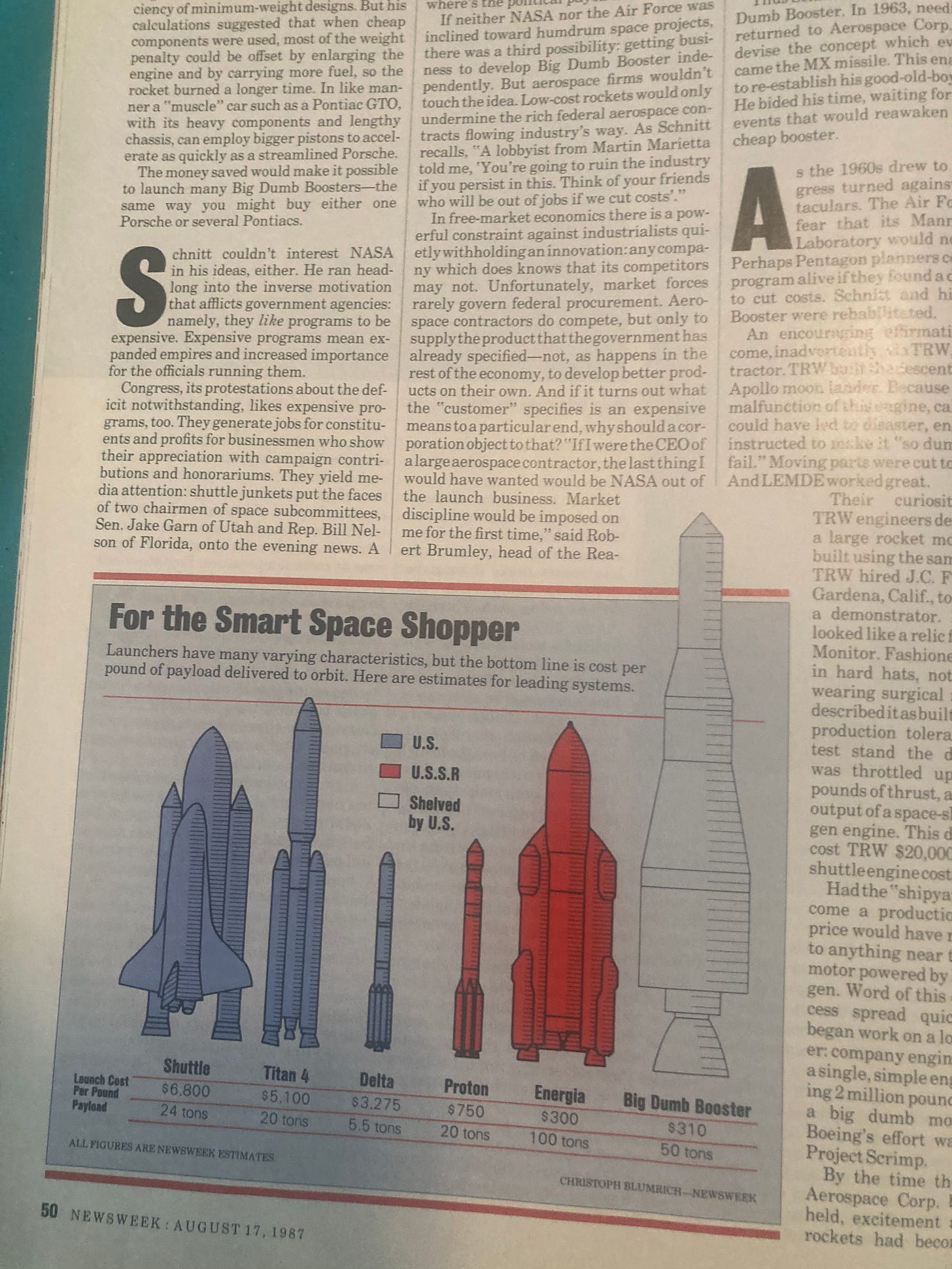

Schnitt called his idea Big Dumb Booster. A Newsweek artist’s conception showed Big Dumb Booster being much bigger than the space shuttle, at about 400 feet – almost exactly the same as Starship today.

The Big Dumb Booster idea was forgotten – until 2023, when SpaceX launched the first Starship. It exploded. This was the launch Musk wisecracked resulted in “rapid unscheduled disassembly.” The second launch got higher before exploding. The third, last week, reached space before disintegrating on reentry.

So Starship is zero-for-three. But then the first U.S. attempt to launch a satellite exploded, and within a few years, satellite and space-capsule launches were routine.

The SpaceX Falcon rocket family is so reliable it carries astronauts to the International Space Station. Here is the most recent such launch

Falcons also fly thousands of small satellites for Musk’s Starlink commercial firm and for U.S. intelligence services. Space analyst Jonathan McDowell counts 5,438 Starlink satellites in orbit – more than all other types of satellites combined.

Success of the Falcon series has brought free-market forces, and price discipline, to U.S. rocketry. The space shuttle cost of about $30,000 per pound delivered to low-Earth orbit compared to the Falcon series cost of about $1,500 per pound delivered.

NASA didn’t care what the space shuttle cost, it just sent the invoice to the taxpayer. Commercial satellite customers do care, and if there is ever to be commercial activity on the moon -- probably not, but possible -- holding down cost will be vital.

Here is my 2003 The Atlantic article about the first private company to put heavy satellites into orbit, the quirky Sea Launch.

Sea Launch shot rockets off a specially built ship sailed to the equator near Hawaii, with only open ocean to the east. Equatorial east-facing launch gives rockets ideal oomph, since Earth rotates west-to-east and spins fastest at the Equator. (Oomph is a technical term.)

Sea Launch was 35-for-38 on rockets reaching orbit. The first stage of the Sea Launch rocket was built in Ukraine. The company went out of business in 2014 when Russia began destabilizing Ukraine.

China has embraced the sea launch idea, in January sending satellites into orbit from a converted container ship. The Chinese project involves large mechanically simple rockets using kerosene or easily stored “solid” fuel.

Powerful yet mechanically simple, the SpaceX Falcon might be called Little Dumb Booster. If SpaceX Starship begins to function properly, all kinds of space enterprise that is today prohibitively expensive will become possible. And Big Dumb Booster will exist after all.

Big Dumb Booster would have run on kerosene, which is not technologically sexy. But if the rocket was really big with huge tanks, fuel mass could compensate for lack of max oomph.

The space shuttle relied on liquid hydrogen propellant, which has the highest possible oomph of any chemical rocket fuel – non-chemical propulsion such as nuclear-ion is a long way off – but is notoriously expensive and hard to work with.

Big Dumb Booster would have used steel for its tanks and structures, rather than aluminum (key to aircraft minimum-weight design) and composites, as did the space shuttle.

Schnitt had been on the team that designed the engines of the Apollo lunar landing module. Because these motors had to operate reliably far, far from any Cape Kennedy technicians, they were engineered, Schnitt told me, to be mechanically simple – “so dumb they couldn’t fail.”

At the moon, they worked flawlessly. Schnitt began to say the Apollo lander’s relatively small engine nozzle could be scaled up to a very big yet simple system.

TRW, then an independent aerospace contractor with a reputation for maverick programs, built a scaled-up lunar lander engine that was surprisingly powerful, cost $200,000 versus $250 million for a space shuttle main engine.

The test was called Project Scrimp. NASA ordered it ended. NASA wanted maximum expense, to appease the big-boy contractors and to create patronage jobs at its centers in Alabama, California, Florida, Ohio and Texas.

Starship on the pad – taller than a Saturn V moon rocket. Photo courtesy SpaceX.

When SpaceX began designing Starship, initially it was to be made from carbon composites – technologically sexy, but costly. Musk switched the main components to stainless steel. Performance dropped a little, cost dropped a lot.

Rather than liquid hydrogen, as propellant Starship uses methanol, a liquid alcohol that is mostly natural gas. Much cheaper than liquid hydrogen, only somewhat less powerful.

Big Dumb Booster’s kerosene and Starship’s methanol are called “storable” propellants. They can be stored at room temperature, and do not corrode pipes and tanks.

Not only are storable propellants a lot cheaper than the kind NASA likes – because they are stable, they can be transferred in space.

Starship designers have in mind launching automated versions of the giant booster into orbit as fuel tankers – into orbit around Earth or the moon. Storable propellants could then be transferred to other spacecraft.

If there is ever a Mars mission – see more below – the ship with people aboard won’t depart until there are already fuel tankers orbiting the Red Planet, as well as hundreds of tons of supplies already on the Martian surface. In principle, lots of Starships could be used as Mars tankers and Mars delivery services.

A sci-fi fully reusable rocket – the Starduster in “Space Angel.”

Big Dumb Booster would have had simple “pressure fed” engines without complex turbos. The SpaceX Falcon employs a similar motor. Starship uses a “full flow staged combustion cycle” which runs cooler and with less pressure than super-complicated NASA engines, so Starship motors can be reused with little reconditioning.

The Air Force experimented with “full flow staged combustion cycle” in the 1990s, partly in response to Schnitt and other advocates of minimum-cost engineering. NASA asked the Air Force to stop, because this engine type would be so much cheaper than space shuttle main engines.

The space booster rating most similar to horsepower is “specific impulse at sea level.” Starship’s relatively simple engines and storable fuel produce a rating of 327 on this scale. The space shuttle’s main engine made 366. So the Starship engine is less powerful – at a fraction of the cost.

If it becomes reliable, Starship will cut the price of putting payload into low-Earth orbit to about $100 per pound. All manner of outer space shenanigans will become affordable!

The Falcon 9, workhorse rocket of SpaceX, also is relatively simple mechanically, using kerosene as primary propellant as Big Dumb Booster would have.

Falcon reflects an important innovation – rather than the first stage burning up in the atmosphere or sinking into the sea, the first stage returns to a landing pad, engines firing a second time to slow the vehicle down.

A SpaceX first stage returning to land upright. Photo courtesy SpaceX.

Reuse makes SpaceX rockets less expensive and able to fly often. Falcon rockets are 309-for-312 -- only three failures, and more successes than any NASA or Air Force launcher. After 257 of the flights, the booster was in good enough condition to be reused successfully.

The plan is for the booster stage of Starship to return to land vertically and be reused. This hasn’t happened in the three tests so far.

SpaceX is such a success, at such lower cost than NASA or Air Force rockets, in part because of testing philosophy.

Concerned about the public-affairs effect of pictures of exploding rockets, NASA tests the boosters it uses (and the ones it supplies to the Air Force) elaborately, going to great lengths to avoid in-flight failures that can be photographed.

As everyone knows, Elon Musk does not care what people think of him or his companies. He green-lighted the kind of flight tests likely to lead to malfunction, but to generate data to perfect systems.

His first rocket, Falcon 1, failed the first three times it was flown. Falcon 1 has been reliable since.

Rocket engines cause a lot of vibration and shock waves. NASA “static tested” engines to observe vibration and shock waves; SpaceX just let rockets fly (over the Atlantic Ocean or Gulf of Mexico, not over populated areas) to see what happens. High bandwidth telemetry – not available to NASA when moon-race rockets were being researched – allows SpaceX to determine exactly how the vibration and shock waves interact in flight.

Each of the second and third Starship launches got farther than the launch before. If the fourth or fifth launch does not fail, Starship will be the most important space news since the final Apollo mission in 1972.

The 1987 Newsweek artist’s conception of Big Dumb Booster (right) alongside the world’s largest launchers. To scale, Big Dumb Booster is the same height as Musk’s Starship.

Suppose Starship does become reliable. What will it do?

First, this would make it official that NASA’s new heavy-lift rocket, the blandly named Space Launch System, is a white elephant.

With about the same power as the Saturn V moon rocket, Space Launch System has flown only once. The good part is the flight went fine. The bad part is SLS is many years behind schedule and $20 billion over budget.

Developing Space Launch System cost about 10 times what SpaceX has spent to develop Starship. When costs are covered by taxpayers, not only is there no market discipline, federal agencies have an incentive to run up the bill.

The Government Accountability Office estimates SLS will cost about $2.5 billion per launch, more than tenfold the likely launch cost of Starship. Musk’s rockets use Big Dumb Booster concepts. SLS uses pricey composites and liquid hydrogen.

Just the bureaucrat-chosen name – Space Launch System – shows NASA has run out of gas regarding manned flight. (NASA science probes continue to do well.) At least the new moon capsule has a great name, Artemis. (Artemis was Apollo’s sister.) If Starship is reliable, the SLS can be put out of its misery.

A reliable Starship could take the new Artemis capsule to the moon, though many flawless Starship flights would be needed before it was be safe to put people aboard.

Somewhat more powerful than the Saturn V, Starship could deliver supplies to any construction project on the moon. Many politicians (including George W. Bush when in the White House) and aerospace contractors want to build a moon base. Think of the billions that would flow to favored congressional districts! If as expected China lands astronauts on the moon, there would be tremendous pressure to one-up Beijing by being first to have a moon base.

It’s hard to think of what a moon base would do, other than cause spending. For Washington, often that’s enough.

There was a base there in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. We don’t need one now.

A moon base definitely would not be a steppingstone to Mars, as some politicians have claimed. Any Mars mission will depart directly from low-Earth orbit to the Red Planet. Stopping at the moon would use up so much fuel, the concept is nonsense. It is possible resources and water could be produced on the moon then fired toward Mars to support a landing there.

And it’s hard to imagine Starship being used to colonize Mars, as Musk often says it will. Even assuming Starship becomes reliable, a spartan Mars colony remains ridiculously impractical.

People will live on Mars someday – but not till several technologies advance by orders of magnitude. Why living on Mars is ridiculously impractical for the time being is spelled out here.

The ridiculous impracticality of living on Mars does not prevent some from fantasizing it will happen soon, a fantasy Musk encourages with statements that are crazy even by his standards.

In 2017 Musk told an interviewer a ticket to Mars on his rocket would cost half a million dollars. Musk is a terrific actor (and comedian, as he showed on SNL) because he was able to say this without bursting out laughing. The ticket would cost tens of millions of dollars per person – with a trillion-dollar surcharge for the Mars base.

Some seem so convinced that climate change will end the world they look to life on Mars for hope. Last week the gloomy-by-design New York Times headlined – of a Starship test flight that ended with all hardware smashed – SPACEX SUCCESSFUL ON THIRD TRY.

Perhaps elites think Mars is a backup planet in case we break Earth. Protecting Earth will be way less costly than decamping to Mars.

The reason is be excited about Musk’s gigantic Starship is that it will make feasible many projects in orbit and in nearby space.

For instance the last two space-based telescopes were sent to locations about three times as far away as the moon. Starship would render practical a large network of space-based telescopes to study the sun, to search the galaxy for life.

If it becomes reliable, Starship will be a game-changer for access to space, more of a game-changer than Tesla is for cars. And it will be Big Dumb Booster sailing the heavens. A shame Arthur Schnitt isn’t around to see it.

New Feature: In Other Substacks

The Belgian intellectual Maarten Boudry shows that, while climate change is scientifically proven and a clear risk, the doomers are engaged in preposterous exaggeration:

Here Boudry proposes 2024 is the best year ever to be born, because positive trends outweigh the negatives.

Bari Weiss’s Free Press – a possessory credit on Substack! – reports the business aspects of SpaceX:

Radley Balko, in a first of three, demolishes claims (including in the Free Press) that Derek Chauvin, the man who killed George Floyd, was the real victim. Balko’s 2013 book Rise of the Warrior Cop is among the top nonfiction works of the last decade.

About All Predictions Wrong

There will be an All Predictions Wrong, on an eclectic range of topic, every Friday all year. There are sometimes bonus editions depending on news events.

Next month there will also be two Tuesday Morning Quarterbacks, on either side of the NFL draft. TMQ returns fulltime when football resumes.

A subscription to All Predictions Wrong includes Tuesday Morning Quarterback, so it’s two-for-one.

I’ve been reading you since the early days of TMQB and I had always assumed that was where I first encountered your writing. But now I realize I first read you in the 1987 Newsweek article. It was the primary research reference in the first term paper I ever wrote as a sophomore in HS. I remember it vividly, the Big Dumb Booster and the pic of the various rockets side by side. Just didn’t realize how early your writing had impacted me. I don’t always agree with your writing on culture and society but I do still appreciate your perspectives. But I always love your takes on science. Thanks for all you do. Was glad to find you on Substack as I had lost track of your writing for several years other than your books.

What a treasure this is week after week (even without football). I have no real interest in rockets etc, and found this week's edition captivating. Please keep up the excellent work--its so hard to find this sort of thing elsewhere.